| FRONT PAGE | NAYARIT NEWS | Tara’ Best Bets |

TRAVEL | HOME & LIVING | MEXICO INSURANCE PRODUCTS |

TRAVEL BUDDIES |

How Mexico’s president won over the working class

“He’s the best . . . he’s helping those who have the least,” Flores said in his shop in the textile-making town whose streets are lined with decorative tissue paper. Flores is one of some 25mn people in Mexico who now receive benefits from a social programme, according to government figures.

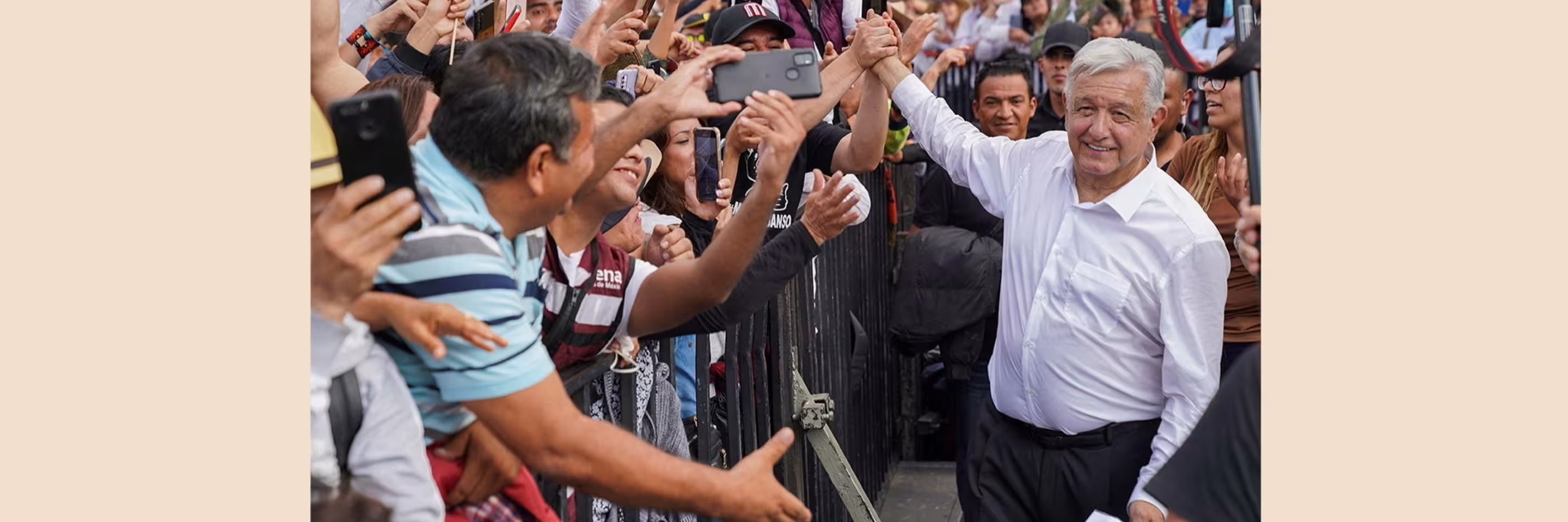

The cash transfers have been a centrepiece of the president’s political project. López Obrador, 70, began his life in politics as a protest leader in his home state of Tabasco before becoming mayor of Mexico City in 2000. He then spent a decade campaigning around the country, losing two presidential votes but building a base among the working class, which helped him to win a landslide victory across demographics in 2018.

As he prepares to hand over power following elections next week, he remains broadly popular, with approval ratings in the mid-60s — despite stagnant growth, some of the region’s worst excess mortality in the Covid-19 pandemic and record numbers of murders. The president, known as “Amlo” for his initials, has retained fierce loyalty among poorer Mexicans who have long resented what they see as an out-of-touch political class tainted by corruption, but do not view the president as part of it.

López Obrador refused the president’s jet and mansion and says he does not have a credit card. The president, who is limited to a single, six-year term in office under Mexico’s constitution, barely travels abroad and is known for riding in a white Volkswagen Jetta and eating in modest snack bars and cafés. Mexico’s smallest state after the capital, Tlaxcala has large swaths of farmland and some factories, indigenous communities and high levels of poverty. The president won here in all three elections he contested, including almost three-quarters of votes in 2018, the second-highest after his home state.

“He likes being with the people,” Herrera said. The government social programmes — targeting the elderly, some farmers and young people — are crucial to López Obrador’s popularity. Social spending is up 30 per cent in real terms since he took office, and is skewed heavily to cash transfers, which are more than three times higher, according to public policy think-tank IMCO. Broader coverage under López Obrador compared with his predecessor means that more people benefit, but the poorest receive relatively less than before.

López Obrador also oversaw a more than doubling of Mexico’s paltry daily minimum wage to 250 pesos ($15), with little negative economic fallout. That helped to bring millions of Mexicans out of moderate poverty: the rate fell to 36 per cent in 2022, from 42 per cent when he took office. Extreme poverty rose slightly, however. López Obrador’s critics see a polarising figure seeking to restore a hegemonic party and undermine democracy.

Urban centres such as Mexico City are divided, with some who thought he was a decent mayor arguing that he has since taken a more radical, intolerant turn. Middle- and upper-class voters are concerned that López Obrador is weakening democracy, with hundreds of thousands marching in defence of institutions such as the Supreme Court and electoral authority in recent months. López Obrador’s base sees it differently.

“There is more democracy now because people participate more,” Flores said. Central to López Obrador’s power is the “mañanera”, an hours-long morning news conference held every weekday. It dominates the airwaves in a country where swaths of the media rely on government advertising. Friendly journalists often pose fawning questions. “You can’t explain what’s happening today in Mexico, nor [López Obrador’s] popularity nor voting preferences, without the mañanera,” said Roy Campos, president of polling group Mitofsky. “At the end of the day, [people] want a president who confronts the powerful and defends the poor, and that’s the narrative he presents every day.”

Like with other populist leaders with a gift for communication, López Obrador has coined phrases that have entered the local lexicon. He likes to condemn the “conservative, bourgeois media”, and when confronted with unflattering statistics says he has “different data”. Critical commentators call him the “Teflon” president, who explains his own failures in terms of obstacles placed in his way by “elites”.

Polls show that security is the top concern for voters in this election, with more homicides and missing people recorded in López Obrador’s term than any other president in Mexico’s history. His supporters agree he has not fixed the problem, but believe he wants to and that the task is too difficult — or that others are responsible for the increase in bloodshed, such as local officials and the judiciary.

“Ms Piña, the judge, lets criminals out, what can the president do?” said Germán Rojas, who runs a cleaning supplies store in Tlaxcala, referring to the supreme court president Norma Piña, who was vilified by López Obrador in his conferences after justices struck down laws passed by his party. López Obrador’s protégé Claudia Sheinbaum, the frontrunner for the next presidency, has promised broad continuity of his policies, and polls suggest she could win a similar proportion of votes.

Two-thirds of those who receive his social programmes plan to vote for Sheinbaum, while almost half of those who do not will vote for opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez, according to an April poll by El Financiero newspaper. Many voters take a negative view of opposition parties, particularly the PRI, which is associated with decades of one-party rule and corruption, a narrative López Obrador fuels in his conferences. The PRI forms part of the coalition led by Gálvez. “The PRI sold the country,” said Doroteo Xelhuantzi, an artisan who makes blankets in Tlaxcala.

“The roads were sold to the Canadians and the oil dished out to the Americans.” Recommended Enrique Krauze Mexican democracy hangs in the balance The June election, which is also for congress and tens of thousands of local posts, has become a referendum on López Obrador’s political project, even though the man himself is not on the ballot for the first time in more than two decades. Though she has vowed to continue his project, Sheinbaum will have to contend with a large fiscal deficit, and the former academic lacks her mentor’s natural communication style.

The president has said he will retire to his ranch, but many of his supporters say they wished the president could run again. Of Sheinbaum and other national leaders of Amlo’s Morena party, Flores the butcher said: “They’ll keep López Obrador’s movement going for now, but in the future — who knows.”

| Insurance for your American or CanadianVehicle while in Mexico | Insurance for your MexicanVehicle |